Introduction

“Conation” from the Latin “conatus; any natural tendency, impulse or directed effort.”

Intelligence measures IQ; emotion measures how you feel. So which part of the brain gets those thoughts and feelings out of your head and applies them to your everyday life?

That little-known aspect is called conation. You’ve probably heard of the cognitive and affective parts of the brain. And while they’re certainly important, those two pieces alone don’t give the full picture. Neither of them drives action, dictating the way you will turn your ideas into real results. Smart people will take action in different ways; looking only at intelligence and how you feel about something doesn’t explain the methods you’ll use to tackle a problem.

And that’s where conation comes in. The conative part of the brain is the third piece of the tripartite mind, the cluster of human instincts that drives creative problem solving. Understand conation and you’ll understand the approaches you’re naturally driven to take. Acting according to your natural abilities will, in turn, maximize your success and well-being.

While conation was accepted by ancient philosophers up through early 20th century psychologists, few concepts concerning conation survived unscathed from subsequent debates. My mission has been to bring conation back to the forefront and teach people how to trust their natural abilities. My research and validated theories make up the bulk of modern research into conation, although there is a rich history of philosophers and academics discussing the concept.

Table of Contents

I. Key Concepts of Conation: An introduction to the role conation plays in your everyday life

II. Kolbe Wisdom™: An overview of the author’s work, which has brought conation into modern-day relevance

III. Kathy Kolbe’s Contribution: A New Beginning: Charting the author’s course along the path that led her to conation

IV. Conation: Wisdom of the Ages: A historical perspective of debates surrounding conation, including an explanation of why you may not have heard of it

V. References: A bibliography detailing sources for further exploration

I. Key Concepts of Conation

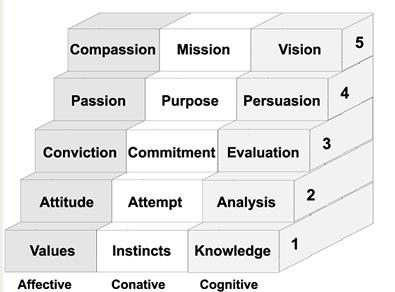

What is conation? Conation is the mental faculty that causes an individual to act, react and interact according to an innate pattern of behaviors. As one of the three elements of human behavior, its function is to convert the affective faculties, which are emotions, preferences or beliefs, and the cognitive faculties, which are learned knowledge and skills, into visible and purposeful performance. It drives us to actually do what the other parts of the mind either make us want to do or know have to be done

Instincts are unalterable. Conation is an internal, unchanging, unconscious attribute. Each person’s instincts drive them to naturally approach problems in particular ways. Theses natural abilities can’t be altered by education, coaching, counseling, self-help manuals, parenting or pleading. They are derived from subconscious, unalterable instincts.

Action is purposeful. Conational actions and reactions are volitional, or purposeful, not a physical, knee-jerk response. When a person wakes up cold, wants to get warm and knows there is a blanket at the end of the bed, it takes a volitional decision to “get conative” – to actually reach down and pull up the blanket. Conative actions become acts of Will when an individual takes self-control over these instinct-driven patterns of behavior. Individuals have no control over which innate talents they have, but they do have power over when they will use their resources. “Taking charge of your own destiny” assumes an individual has the self-determination to direct the use of his or her conative strengths.

Conative MOs reveal strengths. Conative action is powered by a set of attributes or traits that are the modes of a person’s natural method of striving, or modus operandi. A person’s MO dictates how they will naturally take action or respond to problems when given the freedom to be themselves. Conative "modalities," or modes,have been called the bedrock, hard wiring and DNA-equivalent of the mind. Like a fingerprint or blood type, a person is born with this conative MO and can count on it to be there for a lifetime.

Conation sets us apart. Acting, reacting and interacting according to one’s conative bent leads to goal-oriented achievement. Conative action differentiates human beings from lower forms of animals. For other animals, instincts seem to be tied to physical acts rather than to mental faculties over which they can Will themselves to engage at self-determined levels.

Action stems from conation. Some modern brain researchers consider conation the executive function of the brain, located in the frontal cortex, with the responsibility for managing the actions stemming from the other faculties, or brain functions.

Defining the authentic self. Not tempered by cajoling, improved by science or diminished by rejection, my study of conation has led me to believe that conative modes define the authentic self, the core of one’s being, the source of profound self-efficacy and the otherwise elusive element that determines the nature of a human being.

II. Kolbe Wisdom

Our conative talents may be different, but each strength is created equal. Every person’s MO gives them a particular set of talents, and probability dictates that you and I likely have different talents. We may go about doing things differently, but that doesn’t mean one method is superior to the other; on the contrary, if we let each other be ourselves instead of forcing conformity, we’ll have a greater pool of talents to draw from.

What follows are the conclusions I’ve drawn about conation over 30 years of original research. As I told a judge who decided my work is original and therefore copyrightable, these axioms are not facts others have proved, nor are they fiction I have made up. They are truths that have become self-evident through my research.

Kolbe Axioms relating to Individual Actions or MOs

Conative strengths are driven by universal instincts. Each of us has strengths that derive from unconscious instincts, although particular strengths differ from person to person. These talents become observable through purposeful actions. Each person can control when they use their instinctive strengths, which surface when an individual is motivated to strive toward conscious goals.

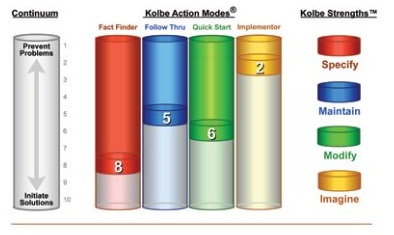

Axiom #2: Four Action Modes® are universal methods of striving

All conative strengths fall into one of four Action Modes used in problem solving.

Kolbe Action Mode Striving Behaviors

Fact Finder Gathering and sharing information

Follow Thru Organizing, arranging and designing

Quick Start Dealing with unknowns, uncertainties and risks

Implementor: Handling tangibles, mechanics and space

Every person takes action in each Action Mode. We all gather information, organize, deal with unknowns and handle tangibles. But the way we approach each of those tasks is naturally different, and that’s what makes up a person’s conative talents. Look at a person’s talents in each Action Mode and you will see the basis of the methods that will work best for them when they are striving to reach a goal.

Axiom #3: Conative strengths determine an individual’s modus operandi or MO. They are based on how individuals operate in each Action Mode.

Each Action Mode has three Zones of Operation, or ways of taking action. Those zones involve using the Action Mode to initiate solutions, accommodating others or preventing problems that come from getting stuck in one type of activity.

-In Fact Finder, a person might research in-depth to develop expertise, gather a moderate amount of information to accommodate what’s asked for or get right to the bottom line.

-In Follow Thru, someone may develop schedules and systems, follow the systems set by someone

else or resist getting bogged down by a set way of doing things.

-In Quick Start, people can dive into new tasks, approach with some caution or take a risk only if deemed necessary.

-In Implementor, a person may naturally work and communicate with their hands, be able

to fix something that’s broken or be able to visualize spatial objects.

Conative strengths are quantifiable through the use of an algorithm that identifies an individual’s natural way of operating. Their MO consists of the zones they fall into in each Action Mode. These zones divide a scale from 1 to 10 on results for conative assessments (the Kolbe Index), enabling individuals to self-identify strengths within each Action Mode. These conative strengths are predictable and reliable.

Each of 12 conative strengths are of equal value in attaining goals through the creative problem solving process. They are distributed equally between genders and among races. Because they are powered by instinct, they are embedded and consistent over an individual’s lifetime. Therefore, an accurate measurement of conative strengths is unbiased by gender, race, and age.

Conative strengths of parents, grandparents and siblings do not predict an individual’s MO. Therefore, it appears that conative strengths are not passed on genetically. Even identical twins have shown no greater probability of having similar MOs than a random sample.

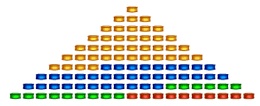

Distribution on the scale of 1 – 10 in a randomly selected, large population generally results in a bell-shaped, or normal, curve, indicating the measurement of a trait of nature rather than nurture.

Axiom #5: Self-efficacy results from exercising control over personal conative strengths

Conative strengths become observable during striving activities; otherwise, they are mere potential. Self-awareness of conative talents paves the way to exercising self-control over when and where to use those strengths. Persevering in their use provides a sense of self-efficacy.

The conative, cognitive and affective parts of the mind all contribute to the Kolbe Creative Process™, which is synonymous with productivity. Each of the three parts of the mind operates independently, yet all three are equally important in contributing to the process.

Different tasks have different levels of importance attached to them. The level of importance attached to a task will determine the amount of energy a person spends on it, resulting in a hierarchy of effort for all three faculties of the mind. This hierarchy is the Dynamynd® of Decision Making. Success in reaching minor goals is necessary to prepare for success in reaching higher-level goals.

Conative strengths are equally strong in every person, even if another faculty of the mind is impaired. However, a disability in any faculty of the mind will impact the creative process, since it requires the integration of all three mental faculties.

Kolbe Axioms relating to Interactions or Relationships

Obstacles that interfere with an individual’s free use of conative strengths limit the potential for success or goal attainment. Striving becomes less joyful and frustrations ensue.

Self-induced conative stress is caused by an individual attempting to work against his or her conative grain. In other words, someone working in a way that doesn’t play to their strengths. It’s like paddling a boat upstream. Much effort is made, with little progress to show for it.

Strain or a depletion of mental energy results from forcing efforts based on false self-expectations. It leads to mental burn-out and low self-efficacy. This can be measured by the Kolbe B™ Index result.

When a number of people on a team are experiencing this Strain, it has measurable negative results, which are identified and quantified in organizational reports by depletion.

Axiom #9: Significant differences in MOs between individuals create conative conflicts

Differences in conative strengths between people can be of great benefit. People with

significant differences in Kolbe Index results can fill in each other's gaps or collaborate by doing what the other won’t do well. However, these differences can also be the source of relationship-damaging conflict if either person considers the other’s conative strengths to be a fault that needs fixing.

Axiom #10: Requirements that reduce a person’s freedom to act on conative strengths diminish performance

Attempts to force an individual to go against a conative grain cause tension and may escalate into individuals acting out or shutting down.

Requirements that do not give individuals the freedom to use their conative strengths cause tension, which is a form of conative stress. In group settings, this diminished performance magnifies and results in a higher probability of meltdown, or collective tension.

Tension is frequently inflicted on highly determined kids whose conative strengths are viewed as weaknesses. When their conative strengths are misidentified as ADD/ADHD, they suffer stress similar to that of workers who are told their conative strengths are inappropriate ways to perform job-related tasks.

Kolbe Axioms relating to Interactions or Group Behaviors

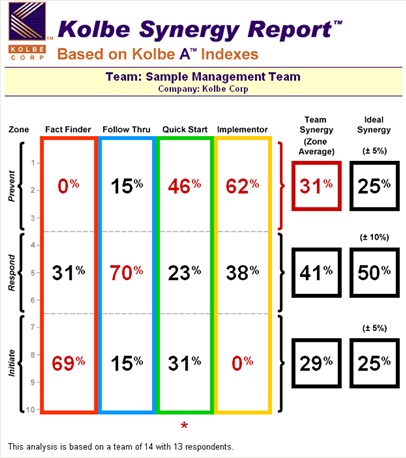

Synergy comes from the right combination of MOs in a group of collaborators. A group that collectively has every zone in each mode will have all the conative talents in its arsenal. An ideal group would reflect the zones of operation as they naturally occur in the population, with 20 percent initiating solutions in any mode, 60 percent accommodating and 20 percent preventing problems. A strategic balance of MOs in a group of collaborators increases the probability of goal attainment.

Axiom #12: Inertia is caused by redundant conative strengths

A group with inertia, or too much energy in one zone of an Action Mode, will show symptoms of low momentum. They will become plagued with inaction, no forward action or a narrow, repetitive approach to problem solving. The group has essentially cloned itself (birds of a feather flock together). They often find false comfort in their sameness, but fail to find the benefits of synergistic conative talents.

Axiom #13: Polarization results when opposite conative strengths pull against each other

Polarization is often present in groups in which participants fight amongst themselves. When conative talents for an Action Mode within a group are at opposite ends of the scale, actions become unproductive as each polar set of talents conflicts without enough accommodating energy. The problem solving methods are so far apart that consensus building is difficult.

Axiom #14: Probability of team success improves as conative strengths are appropriately allocated

High productivity is predicted in organizations with a high percentage of people who are able to contribute their conative strengths. As conative stress, or the inability to contribute conative strengths, increases among people in an organization, so does absenteeism, turnover, dissatisfaction and errors.

III. Kathy Kolbe’s Contribution: A New Beginning

How do I know what I know about conation? Thirty years of research, which have led me to conduct more than 500,000 case studies validating my theories, indexes and methods for helping people thrive using their natural abilities.

But the way I started studying conation actually stemmed from skills I learned from a cognitive expert: my father, E.F. Wonderlic, the originator of cognitive testing for placement and selection. Learning alongside his work gave me the ability to develop a mental measurement. However, that knowledge couldn’t have predicted the way I would develop my next-generation measure of a faculty of the mind he and I never discussed.

What was natural for me was to develop a test of conation before I even knew the word conation. I was doing extensive work with students when I founded Resources for the Gifted, a publishing, training and program development company that was setting the standard for gifted education. Interacting with these kids gave me ample first-hand evidence of the vast differences in actions naturally taken by gifted individuals. This variety of talents was also evident among the mentally challenged youngsters I worked with. All I knew for certain was that the results of what I first named the IF (for IF I ever figure out what I’m measuring) had nothing to do with IQ or emotions.

Every axiom I developed resulted from a discovery process of trial and error that suited my 8 in the Quick Start mode. Being a 6 in Follow Thru led me to systematically chart patterns of behavior I observed. Being a linguist, I sought just the right words to describe the consistent differences that appeared. Turning to a tattered edition of Roget’s Thesaurus inherited from my father, I found the word “conation” – and also that Roget’s seminal work could answer many of my other questions. He had brought order out of the complexity of the English language, classifying words and phrases not alphabetically, but according to ideas. Of his six classifications of ideas, three dealt with the mind: cognitive, affective and volition (with which he used the term conation).

My 2 in Fact Finder went right to the bottom line. Roget’s classification system was the clue I needed to confirm that I was on the right track: I was not alone. The same patterns had been seen by a leader in his field (which was actually botany). Language I chose for the Kolbe Wisdom is based upon Roget’s classifications and on terms I gleaned from basic physics, since conation deals with natural laws of action and reaction, work and energy. What I had named the Implementor mode (in which I have a 4) led me to conduct hands-on field studies in which the Kolbe Index proved reliable in predicting actions and reactions.

IV. Conation: The Wisdom of the Ages

A Historical and Theoretical Overview

A. Three Faculties of the Mind

That the mind has three distinct parts is the “Wisdom of the Ages.” The Ancient philosophers Plato and Aristotle spoke of the three faculties through which we think, feel and act. George Brett in his “History of Psychology” said, “Augustine was not far from the same standpoint…his language at times suggests the same three-fold division of knowing, feeling and willing.”1

Like Plato’s Rationalism, Spinoza’s Homic philosophy focused on an understanding of the three-faculty concept as a necessary prelude to the quest for ideal self-actualization.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the trilogy of the mind was the accepted classification of mental activities throughout Germany, Scotland, England and America. In the first half of the 20th century, it was American psychologist William McDougall who was its primary proponent.

As Ernest R. Hilgard notes in “The Trilogy of Mind: Cognition, Affection and Conation” (1980), McDougall “assumed that his reader was familiar with the classification of cognitive, affective and conative as common-sensical and noncontroversial.”2

In McDougall’s “Outline of Psychology" (1923), he refers to the three-faculty concept as “generally admitted.”3 He said, “We often speak of an intellectual or cognitive activity; or of an act of willing or of resolving, choosing, striving, purposing; or again of a state of feeling. But it is generally admitted that all mental activity has these three aspects, cognitive, affective and conative; and when we apply one of these three adjectives to any phase of mental process, we mean merely that the aspect named is the most prominent of the three at that moment. Each cycle of activity has this triple aspect; though each tends to pass through these phases in which cognition, affection and conation are in turn most prominent; as when the naturalist, catching sight of a specimen, recognizes it, captures it, and gloats over its capture.”4

The Latin “conatus,” from which conation is derived, is defined as “any natural tendency, impulse or directed effort.” As a faculty of the mind, conation is defined by Funk & Wagnalls Standard Comprehensive International Dictionary (1977) as “the aspect of mental process directed by change and including impulse, desire, volition and striving”, and by the Living Webster Encyclopedia Dictionary of the English Language (1980) as “one of the three modes, together with cognition and affection, of mental function; a conscious effort to carry out seemingly volitional acts.” It is also in The 1000 Most Obscure Words in the English Language as “the area of one’s active mentality that has to do with desire, volition, and striving.”

Stanford University’s Richard E. Snow, writing an editorial titled “Intelligence for the Year 2001” (1980), sums up the situation well when he says, “It is not unreasonable to hypothesize that both conative and affective aspects of persons and situations influence the details of cognitive processing . . . A theoretical account of intelligent behavior in the real world requires a synthesis of cognition, conation and affect. We have not really begun to envision this synthesis” (P. 194 “Intelligence for the Year 2001”).5

Among the early statements of the three-faculty concept were Moses Mendelssohn’s (1729-1789) “Letters of Sensation” (1755), in which he said that the fundamental faculties of the soul are understanding, feeling and will.6

Johann Nicolaus Tetens (1736-1805), sometimes called the “Father of Psychology” because of his introduction of the analytical, introspective methods, believed that the three faculties of the mind not only existed, but were an expression of an underlying “respective spontaneity of the mind.”7

Immanuel Kant’s tripartite division of the mind gave psychology the support of the most influential philosopher of his day. In his “Critique of Pure Reason” (1781), “Critique of Practical Reason” (1788) and “Critique of Judgment” (1790), he discussed them transcendentally rather than empirically. In his classificatory scheme, pure reason corresponded to intellect or cognition; judgment to feeling, pleasure or pain, therefore affection; and practical reason to will, action or conation.

He said, “There are three absolutely irreducible faculties of the mind, namely, knowledge, feeling, and desire. The laws which govern the theoretical knowledge of nature as a phenomenon, understanding supplies in its pure a priori conceptions. The laws to which desire must conform, are prescribed a priori by reason in the conception of freedom. Between knowledge and desire stands the feeling of pleasure or pain, just as judgment mediates between understanding and reason. We must, therefore, suppose that judgment has an a priori principle of its own, which is distinct from the principles of understanding and reason.”8

Later, the three-faculty concept showed up in Scotland. In 1854, Sir William Hamilton said, “If we take the Mental to the exclusion of material phenomena, that is, phenomena manifested through the medium of Self-Consciousness or Reflection, they naturally divide themselves into the three categories or primary genera; the phenomena of Knowledge or Cognition, the phenomena of Feeling or of Pleasure and Pain, and the phenomena of Conation or Will and Desire."9

Concurrently Britain’s Alexander Bain (1818-1903) was writing of “The Senses and the Intellect” (1855) and “The Emotions and the Will” (1859), which became the standard textbooks for 19th century British psychology.

Bain said, “The phenomena of mind are usually comprehended under three heads:

I. FEELING, which includes, but is not exhausted by, our pleasures and pains. Emotions, passion, affection, sentiment are names of Feeling.

II. VOLITION, or the Will, embracing the whole of our activity as directed by our feelings.

III. THOUGHT, intellect, or Cognition.”10

In the late 20th Century, physiological aspects of brain functioning reinforce the time-honored three-faculty concept. The micro genetic theory of action as constructed by Gary Goldberg, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Temple University School of Medicine, Moss Rehabilitation Hospital, Philadelphia, PA, for “The Behavioral and Brain Sciences” (1985), describes in detail the Supplementary Motor Area (SMA) and its role in the cortical organ of movement as viewed by neuroscientists. His research provides evidence that suggests SMA is the significant factor in the development of the intention to act and the specification and elaboration of action through its mediation between the medial limbic cortex and primary motor cortex.

Reviewing Goldberg’s work, Jason W. Brown, Department of Neurology, New York University Medical Center, N.Y. (1985), stated:

“The clinical material demonstrates that frontal systems correspond with successive movements in action microgeny. We can infer that an action has a dynamic and hierarchic structure... the internal context of the action is established through links with limbic cognition, a stage of symbolic and conceptual organization in which drive fractionates to partial affects. Space is volumetric; an external world is not yet present. There is incipient purposefulness attached to the action; it becomes goal directed as its object undergoes simultaneous differentiation.”11

That neuropsychologists have only recently taken a closer look at the crucial role the SMA plays in the volitional process might be seen, according to Antonio R. Damasio, Department of Neurology, University of Iowa College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA, in his commentary “Understanding the Mind’s Will” (1985), “... as the fate of higher-order integrative systems.”12

Piaget had referred to conation many years earlier as the mental domain most difficult to differentiate and thus he laid it aside as, until now, have the neuropsychologists. Piaget used his concept of disengagement to refer to the degree to which cognitive activity is independent of affective and conative relationships.13 But as Damasio points out, the “...anatomical and functional knowledge about the SMA and its vicinity will permit us to model the neuronal substrates of the will [his emphasis] and thus overcome a persistent objection of those who favor a dualist position regarding mind and brain."14

As Snow said, “Historically, the concept of ‘conation’ was coordinated with cognition and affect, the three comprising the main domains of mental life. There has been recent interest in the interaction of cognition and affect... But the conative seems to have dropped out of modern psychology’s consciousness. It deserves reinstatement and research.”15

B. Conation

Plato’s Being, Brentano’s Psychological Acts, Wundt’s Processes, the transitive status of James, the purposefulness of Stout, the propensities of McDougall and cathexes of Freud are all variants of a common recognition of the mind as active. All separate the conative part of the mind from passive thinking and feeling.

The Encyclopedia of Psychology “Motivation: Philosophical Theories” says, “Some mental states seem capable of triggering action, while others — such as cognitive states — apparently have a more subordinate role [in terms of motivation] ... some behavior qualifies as motivated action, but some does not.”16

Hume in his “Treatise of Human Nature,” Book II, Part III, Section II, argued that intellectual awareness or “reason” cannot move us to do anything.17

Locke in 1690 said:

“Volition or willing is an act of the mind directing it through to the production of any action, and thereby exerting its power to produce it... He that shall turn his thoughts inward upon what passes in his mind when he wills, shall see that the will or power of volition is conversant about nothing but our own actions; terminates there; and reaches no further; and that volition is nothing but that particular determination of the mind, whereby, barely by a thought, the mind endeavors to give rise, continuation, or stop, to any action which it takes to be in its power."18

Further, from the introduction to B. S. Woodworth’s investigation into volition: “An impelling interest attaches to the study of Human Volition. No other of man’s activities reaches so far in its consequences, both to the individual and to society, as does that of his Will. History is a record of its strivings and achievements and failures. The social and ethical sciences are founded on it. Its importance in education can scarcely be exaggerated. Culture, civilization itself, depends on the regulated volitions, repressions, and inhibitions of individuals and nations. All these activities come under the meaning of the term ‘Will’ as it has been sanctioned by long and universal usage. It is vital, therefore, that our knowledge of Will-activity should be as exact and scientific as possible. Yet there is no field of psychology so slightly tilled as that which deals with volition.”19

For many of the early philosophers and psychologists, conation was the instigation and regulation of behavior. It was what impelled action, whereas the cognitive compelled.

Spinoza, Hobbs and Descartes were all involved in a goal-directed theory of motivation. An essential part of that theory was Spinoza’s delineation of conatus as basic endeavor. He said it was the source of all striving, longing, ambition and self-expression. It was the tendency for a person to persist against obstacles. For these philosophers, conation was the very essence of the person, for, as Spinoza said, it was through conation that one persevered in one’s own being.

C. F. Stout (1913) said that conation, as goal-directed striving or purposive activity, involved two meanings of the goal or end of the striving. “One is the obtaining of means and the other making affective [sic] use of the means.”20

Kurt Goldstein (1963) included conation in his concept of “Coming to Terms with the World.” He called conation “self-actualization,” the matrix of all motivation of “basic drive” which accounts for all human activity.21

In Freud’s theory of the conative nature of character, he recognized what great novelists and dramatists had always known. That, as Balzac put it, the study of character deals with “the forces by which man is motivated. That the way a person acts, feels and thinks is, to a large extent, deemed by the specificity of his character and is not merely the rational response to realistic situations. That man’s fate is his character.”22

Conative Modes - Instinctive and Distinctive

Erich Fromm in his work on “Human Ethics” discussed the conative nature of man by saying the way man achieves virtue is through the active use he makes of his powers. Uncertainty (the cognitive) is the very condition to impel a man to unfold his power. If he faces the truth without panic, he will recognize that there is no meaning to life except the meaning man gives his life by unfolding his powers, by living productively; and that only constant vigilance, activity and effort can keep us from failure in the one task that matters — the full development of our powers without the limitations set by the laws of our existence… “to be himself and for himself to achieve happiness by the full realization of those faculties which are peculiarly his — of reason, love and productive work.”23

Psychologist McDougall’s definition of character (1923) was: “The system of directed conative tendency exemplified by the finest type is that which is complex, strongly and harmoniously organized and directed toward the realization of higher goals or ideals.”24

The unifying thread over the centuries as philosophers have looked at conation is the thought that “by your acts ye shall be known,” and by placing it as the dominant mode in determining character: ”actions speak louder than words.”

A good man for Aristotle was a man who by his activity, under the guidance of his reason, brought to life the potential specific of man.25 In the consistent use of the term “productivity” to mean the use of one’s powers or one’s capacity, there has been an underlying assumption that this capacity was both inherent and definable.

From Fromm’s “productive orientation” was “a fundamental attitude, a mode of relatedness in all realms of human experience. It covers mental, emotional and sensory responses to others, to oneself and to things. Productiveness is man’s ability to use his powers and to realize the potentialities inherent in him ... he must be free and not dependent on someone who controls his powers... he can make use of his powers only if he knows what they are, how to use them and what to use them for... they [must not be] masked and alienated from him.”26

That man’s conation, productivity, character or mode of doing comes in modes that are both instinctive and distinctive has also been a prevalent thought among philosophers and psychologists. Michael Malone in his book “Psychetypes” said, “One of the ways a person can become neurotic (that is, unable to realize his own potentialities) is by failing to develop his natural typology. Furthermore, it is difficult for people to develop happily when their natural typology is not recognized or respected by others. By providing a language for experience, a theory of psychetypes enables us to communicate across our typological worlds and thereby come to understand and accept the validity of our differences.”27

In “Endeavors in Psychology,” Henry Murray uses conation to denote each persistent effort (intention, volition, act of willing) to attain a specific goal. “Conations,” he said, “are perhaps a long integrated series, deriving their force from one or more needs...the general motivating factor is need — tension — but the chief integrating factor is the conation which directs the organization of muscular and verbal patterns toward the attainment of a definable effect, or subeffect.”28

Murray goes on to say, “the personality is almost continuously involved in deciding between alternative or conflicting or tendencies or elements…the most pressing and demanding are conflicts between different conations. Since conations (purposes) derive their energies from needs...or alternative goal-objects, conations are specific in respect to goal-place or goal-object.29

In the late 1940’s, Raymond Cattell attempted to explain conational modalities in a complex set he called the “dynamic lattice.” What McDougall had called instinct or propensity, Cattell termed an “erg.” An erg, Cattell said, was an innate psychological/physical disposition, or inborn disposition, which permits its possessor to acquire reactivity to certain classes of objects more readily than others, to experience a specific emotion in regard to them and to set on a course of action which ceases more completely at a certain specific goal activity. His dynamic lattice analyzes the interconnections among ergs (conative) and sentiments (affective) to show purposive sequences.30

His philosophy of dynamic psychology stressed the importance of motivation or fundamental energy in psychic life. Only by looking at man in dynamic rather than static conditions did he feel conation could play its appropriate role.

In the context of our rapidly changing environment, conation becomes a key element in the interpretation of human behavior. For centuries, philosophers and scientists have talked about it, but the dynamic requirements which lead us to strive under ever more challenging conditions have required an entrepreneurial mind to not only research the historical perspective of its existence, but to produce operative models with practical applications.

As to proving empirically the existence of specific traits, Albert Mehrabian in Analysis of Personality Theories says: “One cannot observe a habit, a need, or a trait. One only infers these from observable behavior…conceptual labels subsume several classes of behaviors…factor analysis makes it possible for theorists to evolve a set of habits which satisfy these assumed properties... to identify clusters of behaviors.”31

Jung’s type theory (1912) involved four subclasses—thinking, feeling, sensation and intuition—which cut across his major categories of introvert and extrovert. Freudian writers Friedman and Goldstein found this classification arbitrary and had difficulty in “operationalizing” the function type constructs.32

The difficulty, it would seem, arises from a lack on Jung’s part of incorporating the conative as a clearly delineated aspect of the mind. That may well be why his main distinction between introversion and extroversion has been the more lasting contribution of his work.

Chanin and Schneer found Jung’s personality dimensions (1923) particularly germane to this question of mode predisposition as they reflect an individual’s preferred mode of perception, decision-making, approach and orientation.33

As Kilmann and Thomas (1975) note, this set of personality dimensions is similar to the process model of conflict. For instance, Pondy (1967) said, “...individual differences in psychological tendencies toward these processes [can be] expected to influence the conflict-handling modes which the individual chooses in a given situation.”34

McDougall, as so many others aware of conative traits, expressed the need for giving them specificity. “...at the standpoint of empirical science, we must accept these conative dispositions as ultimate facts, not capable of being analyzed or of being explained.

“When, and not until, we can exhibit any particular instance of conduct or of behavior as the expression of conative tendencies which are ultimate constituents of the organism, can we claim to have explained it (the purposive process).”35

The case has been made for defining Modes within the conative domains. That Jung and others have not separated out the conative and that, therefore, instruments based on such theories have not thoroughly measured such Modes may have to do with the very conative nature of those philosophers and psychologists who have held the mind as their domain. The conative Modes of most Ivory Tower philosophers and psychologists, those who could strive in the research environment, would lead to this bias.

For as Baken put it: “...there is a fact concerning human functioning that is rarely taken into account: that human beings make use of their generalizations concerning the nature of human functioning in their functioning.”36

C. The Three-Faculty Concept: Retreat and Reemergence

While the three-faculty mind concept has deep historical roots, discussion and investigation into the conative faculty dwindled in the mid 20th century to the point of threatening acceptance of the concept altogether. See Snow & Jackson, Individual Differences in Conation: Selected Constructs and Measures, 1997; Gerdes, Conation: the Missing Link in the Strengths Perspective, 2006; Militello, Gentner, Swindler & Beisner, Conation: Its Historical Roots and Implications for Future Research, 2006.

Hilgard traces the retreat from discussion of the three-faculty concept directly to McDougall: “With McDougall the history of the trilogy of the mind appears to have ended...”37

Hilgard goes on to say, “When we look at contemporary psychology from the perspective of cognition, affection, and conation, it is obvious immediately that cognitive psychology is ascendant at present, with a concurrent decline of emphasis upon the affective-conative dimensions... some price has been paid for it. Information processing and the computer model have replaced stimulus-response psychology with an input-output psychology. In the process, some dynamic features such as drives, incentive motivation, and curiosity have been more or less forgotten.”38

B. S. Woodworth in his statement relating to the study of volition said, “We have nothing in this line that can compare with the immense amount of work done on the relation of perception to the stimulus perceived, or... that can compare in completeness with the work done and still being done in all departments of sensation.”39

But the 20th century interest in the cognitive cannot fully explain the retreat from discussion of the conative, for it was back in 1878 that Mark Hopkins, who served as president of Williams College, wrote “An Outline Study of Man” (1878), in which he expressed concern about an overemphasis of cognition.

“Until the intellect is placed by the community where it belongs; and made subordinate to the sensibility and the will, we shall find that mere sharpness, shrewdness, intellectual power, and success through these, will be placed above those higher qualities in which character consists, and success through them.”40

So it was over a hundred years ago that others were saying that success could be interpreted as the freedom to be oneself. How, then, did the intellectual community turn its back on the three-faculty concept? Was it because, as Malone said, McDougall, the modern-day champion of conation, stood outside of scientific responsibility (largely due to his work in extrasensory perception, ESP) and was regarded as an anachronism and menace? Or was it because McDougall’s contemporaries were delving deeply into the cognitive domain, which was thought to be the key to differentiating personnel roles to be played in the military effort? Perhaps it was because so much work had been done to classify, assess and even quantify the cognitive and affective domains.

In the closing years of the 20th Century, W. Huitt stated that “[conation] is absolutely critical if an individual is to successfully engage in self-direction and self-regulation.” (Huitt, Conation As An Important Factor of Mind, 1999)

I concurred with him completely. Few others, however, were paying much attention.

Nevertheless, there was hope. While courses on conation were still not being taught at the university level, business writers were calling for efforts to identify natural abilities, consultants were coaching people on how to trust their instincts, and innovators in education were seeking ways to help students learn through their individual learning styles.

It is perhaps as difficult to explain and trace the concept’s re-emergence as it is to pinpoint reasons for its decline. However, some evidence can be found in the consistent discussion of practical application in the articles and books written on the subject. It seems that those developing the understanding of conation are drawn to the necessity of incorporating it when attempting to adapt academic theories of human behavior for practical application.

While I worked to train professionals from around the world in what came to be called the Kolbe Wisdom, books I wrote on the subject reached parents, job seekers, retirees and others who had previously been left out of the discussion. It was a start.

There is a long way to go.

FOOTNOTES

1.) Hilgard, E.R. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences, 16, 107-117.

2.) Hilgard, E.R. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences, 16, 107-117.

3.) Hilgard, E.R. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences, 16, 107-117.

4.) McDougall, W. (1923). An outline of psychology. London: Methuen.

5.) Snow, Richard E. (1980). Intelligence for the year 2001. Intelligence, 4, 185-199.

6.) Hilgard, E.R. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences, 16, 107-117.

7.) Hilgard, E.R. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences, 16, 107-117.

8.) Hilgard, E.R. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences, 16, 107-117.

9.) Hamilton, W (Ed.) (1854). Collected works of Dugald Stewart Vol I, Edinburgh: Thomas Constable.

10.) Hilgard, E.R. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences, 16, 107-117.

11.) Brown, J.W. (1977). Mind, brain and consciousness: The neuropsychology of cognition. New York: Academic.

12.) Damasio, A. (1985). Understanding the mind's will. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 8(4), 589.

13.) Mehrabian, A. (1968). An analysis of personality theories. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

14.) Damasio, A. (1985). Understanding the mind's will. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 8(4), 589.

15.) Snow, Richard E. (1980). Intelligence for the year 2001. Intelligence, 4, 185-199.

16.) Corsini, R. J. (1984). Encyclopedia of psychology (4 volume set). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

17.) Corsini, R. J. (1984). Encyclopedia of psychology (4 volume set). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

18.) Goldberg, G. (1985). Supplementary motor area structure and function: review and hypothesis. Behavior and Brain Sciences, 8 567–616.

19.) Woodworth, R.S. (1926). Dynamic psychology. In C. Murchison (Ed.), The psychologies of 1925 (pp. 111-126). Worcester, MA: Clark University Press).

20.) Malone, M. (1977). Psychetype. New York, NY: Pocket.

21.) Malone, M. (1977). Psychetype. New York, NY: Pocket.

22.) Malone, M. (1977). Psychetype. New York, NY: Pocket.

23.) Malone, M. (1977). Psychetype. New York, NY: Pocket.

24.) Malone, M. (1977). Psychetype. New York, NY: Pocket.

25.) Wertheimer, M. (1945). Productive thinking. New York: Harper.

26.) Wertheimer, M. (1945). Productive thinking. New York: Harper.

27.) Malone, M. (1977). Psychetype. New York, NY: Pocket.

28.) Murray, H. (1981). Endeavors in psychology. New York: Harper & Row.

29.) Murray, H. (1981). Endeavors in psychology. New York: Harper & Row.

30.) Cattell, R. (1950). Personality: A sistematic theoretical and actual study. New York: McGraw-Hill.

31.) Mehrabian, A. (1968). An analysis of personality theories. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

32.) Malone, M. (1977). Psychetype. New York, NY: Pocket.

33.) Chanin, M. N., & Schneer, J. A. (1984). A study of the relationship between the Jungian personality dimensions and conflict-handling behavior. Human Relations, 37.10, 863-879.

34.) Chanin, M. N., & Schneer, J. A. (1984). A study of the relationship between the Jungian personality dimensions and conflict-handling behavior. Human Relations, 37.10, 863-879.

35.) McDougall, W. (1923). An outline of psychology. London: Methuen.

36.) Snow, Richard E. (1980). Intelligence for the year 2001. Intelligence, 4, 185-199.

37.) Hilgard, E.R. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences, 16, 107-117.

38.) Hilgard, E.R. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences, 16, 107-117.

39.) Woodworth, R.S. (1926). Dynamic psychology. In C. Murchison (Ed.), The psychologies of 1925 (pp. 111-126). Worcester, MA: Clark University Press).

40.) Hilgard, E.R. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences, 16, 107-117.

V. References

Atman, K. S. (1997). The role of conation in distance education enterprise. The American Journal of Distance Education, 191, 14-24.

Atman, K. On goal setting and achievement. Pitt Magazine. Retrieved March 30, 1998, from University of Pittsburgh online magazine: http://www.univ-relations.pitt.edu/pittmag/mar95/m95classes.htm

Bagozzi, R. (1992). The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55.2, 178-204.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundation of thought and action: A social-cognitive theory. Saddle River NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1991). Self-regulation of motivation through anticipatory and self reactive mechanisms. In R.A. Dienstbier (Ed.) Perspectives on motivation, Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Lincoln University Nebraska Press.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman

Beisner, Gary et al. (2006). Conation: Its historical roots and implications for future research.

Boodin, J. E. (1908). Energy and reality, II: The definition of Energy. The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods, 5.15, 393.

Brand, C. (2005). William McDougall (1871-1938): Heterodox and angry with psychologists by nature, nurture and circumstance. Retrieved October 20, 2005 from http://www.cycad.com/cgibin/pinc/july97/brand-mcd.html

Brett, G.S. (1921). A history of psychology, medieval and early modern period. London George Allen an Unwin.

Brown, J. W. (1977). Mind, brain and consciousness: The neuropsychology of cognition. New York: Academic.

Cattell, R. B. (1947). The ergic theory of attitude and sentiment measurement. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 7.2, 221-223.

Cattell, R. (1950). Personality: A sistematic theoretical and actual study. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Conway, C.G. &Howard, G.S. (1986). Can there be an empirical science of volitional action? American Psychologist, 41.11, 1242.

Chanin, M.N. & Schneer, J.A. (1984). A study of the relationship between the Jungian personality dimensions and conflict-handling behavior. Human Relations, 37.10, 863-879.

Corsini, R.J. (1984). Encyclopedia of psychology (4 volume set). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Cudworth, R. (1788). Treatise of freewill. London: John Parker.

Damasio, A. (1985). Understanding the mind’s will. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 8.4, 589

Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason and the human brain. NY: Harper Collins.

Deci, E.L. & Ryan, R.M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11.4, 229

Dibblee, G.B. (1929). Instinct and intuition, a study in mental duality. pp. 25-27

Fitzpatrick, E. L. (2000). Forming effective teams in a workplace environment. Retrieved February 13, 2008, from The University of Arizona, Department of Systems & Industrial Engineering Website: https://e.kolbe.com/_shared/elements/research-validity/university-arizona-kolbe-research.pdf

Freud, S. (1923/1960). The ego and the id. J. Riviere (Trans.), J Strachey (Ed.) New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Friedell, Morris (2000) Potential for Rehabilitation in Alzheimer’s Disease Retrieved February 28, 2008 from http://members.aol.com/MorrisFF/Rehab.html

Friedrich, O. (1985, January). Seven who succeeded. Time.

Gerdes, K. (2006). Conation: The missing link in the strengths perspective.

Giles, I.M. (1999). An examination of dropout in the online, computer-conferenced classroom. Retrieved February 13, 2008 from http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/theses/available/etd-041999-174015/

Goldberg, G. (1985). Supplementary motor area structure and function: Review and hypothesis. Behavior and Brain Sciences, 8, 567-616

Goldberg, G. (1987). From intent to action, evolution and function of the premotor systems of the frontal lobe. IRBN Press.

Hamilton, W. (1860). Lectures on metaphysics. Boston: Gould and Lincoln.

Heckhausen, H & Kuhl, J. (1985). From wishes to action: The dead ends and shortcuts on the long way to action. In M. Frese & J Sabini (Eds.) Goal-directed behavior: Psychological theory and research on action. (pp. 134-159). Hilldale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hershberger, W. A. (1988). Psychology as conative science. American Psychologist, 43.10, 823-824

Hilgard, E. R. (1980). The Trilogy of the mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences, 16, 107-117.

Hoffman, E. (201). Psychology testing at work. How to use, interpret, and get the most out of the newest tests in personality, learning style, aptitudes, interests, and more! McGraw Hill.

Huitt, W. (2001). Why study educational psychology? Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Retrieved Feb. 13 2008, from http://chiron.valdosta.edu/whuitt/col/intro/whyedpsy.html

Huitt, W., & Cain, S. (2005). An overview of the conative domain. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Retrieved Feb. 13 2008 from http://teach.valdosta.edu/whuitt/brilstar/chapters/conative.doc

Humberto, N. (1970). Basic Psychoanalytic concepts on the theory of instincts.

Jackson, D. N. III (1998). An exploration of selective conative constructs and their relation to science learning. CSE Technical Report. 437. Los Angeles: Center for the Study of Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing.

James, W. (1890). Principals of psychology. New York: Holt.

Jung, C. (1923). Psychological types. New York: Harcourt Brace.

Jung, C. (1970). Collection works of C. G. Jung, 4, 111-128. Princeton University Press.

Kanfer, R. (1988). Conative processes, dispositions, and behavior: Connecting the dots within and across paradigms. In R. KR. Kanfer, P. Ackerman, & R. Cudeck (Eds.) Abilities, motivation & methodology: The Minnesota symposium on learning and individual differences. Hilldale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kant, I. The critique of practical reason. (translated by Thomas Kingsmill Abbott).

Kazdin, A. E. (2000). Encyclopedia of psychology. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association. New York: Oxford University Press

Kolbe, K. (1989). Wisdom of the ages: Historical & theoretical basis of the Kolbe concept. Phoenix, AZ: Kolbe Concepts, Inc.

Kolbe, K. (1990). The conative connection. Reading, MAL Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Kolbe, K. (1993). Pure instinct. NY: Random House / Times Books.

Kolbe, K. (June 2000). Lecture notes. Stanford Graduate School of Business, Executive Education Program.

Kolbe, K. (2004). Powered by instinct. Monumentus Press.

Kolbe, K. (2005). Perfectly capable kids. Presentation to Kansas State Department of Education.

Kolbe, K. (2005b). Kolbe axioms. Unpublished paper.

Kolbe, K., Young, A.M., & Gerdes, K.A. (March 2008). Striving instincts and conative abilities: The test-retest reliability of the Kolbe A™ Index. Annual Meetings of the Western Academy of Management, Oakland, CA.

Kolbe.com (2005). Retrieved October 2005 from http://www.kolbe.com.

Kolbe certification manual (2008). Phoenix: Kolbe Corp.

Kolbe professional growth seminar Kolbe wisdom – Kolbe paths to success Phoenix: Kolbe Corp. (2002)

Kolbe statistical handbook: Statistical analysis of Kolbe indexes Phoenix: Kolbe Corp (2002)

Kupermintz, H. (2002). Affective and conative factors as aptitude resources in high school science achievement. University of Colorado at Boulder/CRESST, pp 123-137. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Lazarick, D. L. et al (1988). Practical investigations of volition. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 35.1, 16

Lundholm, H. (1934). Conation and our conscious life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Malone, M. (1977). Psychetypes. New York, NY: Pocket.

McDougall, W. (1923). An outline of psychology. London: Methuen.

McDougall, W. (1908, reprinted 1963). An introduction to social psychology. London: Methuen & Co Ltd.

Mehrabian, A. (1968). An analysis of personality theories. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Miller, G. quoted in Zhu, J. (2003). The conative mind: Volition and action. University Waterloo: Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.

Mueller, R.J. (1988). A study of conative capacity in normal and disturbed at-risk high school students. Doctoral Dissertation University of Pittsburg.

Murray, H. (1981). Endeavors in psychology. New York: Harper & Row.

Peters, R.S. (1962). (Ed) Brett’s history of psychology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Plato. (1937/380 B.C) The dialogues of Plato. New York: Random House.

Poulsen, H. (1991). Conations: On striving, willing and wishing and their relationship with cognition, emotions and motives. Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press.

Roget, P.M. (1852). Thesaurus of English words and phrases. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co. Publishers.

Schatzki, T.R. (1991). Elements of a wittgensteinian philosophy of the human sciences. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic.

Scheerer, E. (1989). On the will: An historical perspective, In W.A. Hershberger (Ed), Volitional action: Conation and control. New York: Elsevier Science.

Schopenhauer, A. (1910). On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason; And on the will in nature. Two essays translated by Karl Hillebrand. London: G. Bell & Sons.

Schur, N. (1990). 1000 most challenging words. New York: Ballantine Books.

Schavelson, R.J., Kupermintz, H., Ayala, C., Roeser, R.W, Lau, S., Haydel, A., Schultz, S., Gallagher, L. & Quihuis, G. (2002). Richard E. Snow’s remaking of the concept of aptitude and multidimensional test validity: Introduction to the special issue. Educational Assessment, 8.2, 77-99.

Silverman, L.K. (1998). Two ways of knowing. Denver: Love.

Snow, R.E. (1980). Intelligence for the year 2001. Intelligence, 4.3 Jul-Sep.

Snow, R.E., (1994). Abilities in academic tasks. In R.J. Sternberg & R.K. Wager (Eds), Mind in context: Interactionist perspectives on human intelligence, pp. 3-37. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Snow, R.E., & Jackson D.N. (1993). Assessments of conative constructs for educational research and evaluation: A catalogue. National Center for Research on Evaluation (CRESST). CSE Technical Report, 447. Los Angeles, CA.

Snow, R.E., Corno, L. & Jackson, D. III. (1996). Individual differences in affective and conative functions. In D.C. Berliner & R.C. Calfee (eds.), Handbook of psychology. (pp. 243-310). New York: Macmillan.

Sternberg, R.J. (1987). Beyond IQ: A triarchic theory of human intelligence. Cambridge, MA: Press.

Stewart, D. (1854). Collected works of Dugald Stewart. Ed Sir William Hamilton, Vol 1. Edinburgh: Thomas Constable.

Swatzwelder, H. Scott. (2004) Certain Components of the Brain’s Executive Functions are Compromised Early in Abstinence Medical News Today 15 Sep. 2004 http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/13418.php

Thomas, R. (February 18, 1998). Statistical report on the Kolbe indexes. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University.

Tort, M. (1974). The Freudian concept of representative (reprasentanz). (This article reproduces the text of a seminar paper on psycho-analysis given at the Ecole Normale Superieure in March 1966). Oxford: Basil Blackwell & Mott LTD.

Vessels, G., & Huitt, W. (2005). Moral and character development. Presented at the National Youth at Risk Conference, Savannah, GA, March 8-10. Retrieved Feb. 13 2008, from http://chiron.valdosta.edu/whuitt/brilstar/chapters/chardev.doc

Wertheimer, M. (1945). Productive Thinking. New York: Harper.

Woodworth, R.S. (1926). Dynamic psychology. C. Murchison (ed.) The psychologies of 1925. (pp. 111-126). Worcester, MA: Clark University Press.